by Myra Brosius

Among our many ministers, Robert C. Galbraith holds a distinctive place. Beginning in 1853, he served Govans for twelve years leading up to and through the Civil War. By many accounts, he was a bright, industrious, and dedicated minister. One of Rev. Galbraith’s most compelling qualities was his call to minister to “negroes” during our country’s tragic era of slavery. Equally intriguing is a personal scandal involving race that arguably, may have contributed to his leaving Baltimore after the Civil War.

After graduating from Princeton Seminary, Galbraith ministered to “negroes” for over two decades, beginning in southern Virginia. He came to Baltimore in 1849 answering the call as the first pastor at Madison Street (now Madison Avenue) Presbyterian Church–the first black Presbyterian church in Baltimore. Later, while serving at Govans, Eliza Ridgely of Hampton Plantation in Towson hired Galbraith to preach to the enslaved there. His tenure at Hampton ended curiously, however, when Ridgely “dismissed [Galbraith] for marrying a woman believed to have African blood.”

Galbraith’s commitment to preaching to “negroes”, and his discharge from Hampton raises many questions:

- What was his message when preaching to the enslaved?

- Did he indeed marry a woman “with African blood?”

- If so, who was she, and what might this tell us about his character?

While we don’t have direct answers to these questions, we can make an educated guess by examining Galbraith’s heritage and influences throughout his life. In doing so we learn the stories about the Scotch-Irish and Presbyterianism, the reaction of the Church to the moral dilemma of slavery nationally and locally, and one man’s journey to align his life with his values at a difficult time.

Preaching to the Enslaved in Antebellum Maryland

During the antebellum period and through the Civil War, pastors preached to the enslaved with differing agendas. Some used the Bible to defend slavery and demonstrate how Europeans were destined to civilize and save the “heathen blacks”—to mold behaviors to keep the enslaved subservient to whites, and to quell rebellion. Others sought to spread the good news of the gospel with messages of hope and redemption. These trends aligned along geographic and political lines; leading up to the war, many southern preachers increasingly supported slavery. Maryland being a border state, citizens and churches alike were split between loyalties. Galbraith grew up in Pennsylvania and preached to “negroes” in Virginia and Maryland. What was he called to preach?

Robert’s Ancestry and Childhood

Cultural experiences influenced northerners and southerners as they grew up with different exposures to the practice of slavery. While no one’s hands were clean of the sin of the United States slave-based economy, northerners were more isolated from the direct atrocities and perhaps less attuned to how their economic fortunes benefited from the south’s cotton industry. Galbraith grew up in Pennsylvania amidst the Scots-Irish of Pennsylvania with a father in the ministry. His maternal grandfather was also a Presbyterian minister.

In the 17th century many Presbyterian from Scotland – at that time part of Great Britain – moved to the Ulster province of Ireland to colonize the area. Conditions deteriorated in their new home and substantial numbers immigrated to the colony of Pennsylvania in the 18th century, where they came to be known as Scots-Irish. Robert’s great-great grandfather, Lt. Col. James Galbraith Jr. (1703-1786), an immigrant, was a Pennsylvania frontiersman and according to historical records, a “man of note,” a justice in Lancaster County who fought in the French and Indian war.

The Scots-Irish greatly influenced settlement patterns of the Pennsylvania frontier, making Presbyterians one of the largest denominations in colonial America. While leaders of the Pennsylvania colony welcomed the Scots-Irish as a means to settle the Pennsylvania frontier, sadly, this expansion of the British colony came at the expense of the indigenous people such as the Lenape and Susquehannock tribes.

Robert was born in 1811 in the town of Indiana, Pennsylvania. When he was four years old, the family moved to Hollidaysburg, a small hamlet in the foothills of the Allegheny mountains along the Juniata River where his father James accepted a pastorship in a log-built church. Hollidaysburg consisted of a few houses and a tavern along a narrow road where on occasion a Conestoga wagon passed through.

While growing up in Hollidaysburg, slavery was not a part of Robert’s family life and likely did not have a presence in the community, thanks in large part that Pennsylvania passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery (AGAS) in 1780. To present-day Americans Pennsylvania is often thought to have been on the right side of slavery, however that was not always the case; in 1750, the colony had over 6,000 enslaved people.

When the state passed AGAS, they set an important precedent. Shortly thereafter Massachusetts implemented immediate emancipation and by 1804 all other northern states enacted laws for gradual emancipation (emancipation in Maryland did not occur until 1864). By 1820, when Robert was nine years old, about two hundred people were enslaved in Pennsylvania with a population of one million.

In the tiny village of Hollidaysburg, Robert received a classical education. According to Norton in the History of Presbyterianism (1879):

“He learned to read, write, and cypher in an old log schoolhouse on the banks of the Juniata, …. and was taught Ross’ Latin grammar so thoroughly by his father that when he went to the preparatory school, at Jefferson College in 1828, he soon overtook the class that was six months in advance.”

Jefferson College, founded by Presbyterians, was chartered in 1802 in part to support the long-standing tradition of an educated clergy. Early supporters of Jefferson College included donors, trustees, and reverends, who enslaved people.

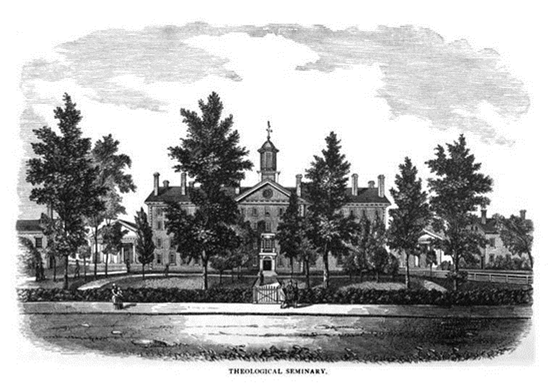

The Princeton Influence

After finishing college, Galbraith attended Princeton Seminary—the first Presbyterian seminary of the United States, founded in 1812. The school had a complicated relationship with the institution of slavery. Princeton struggled with reconciling the immorality of slavery with a practical solution that their white supremacist culture could embrace.

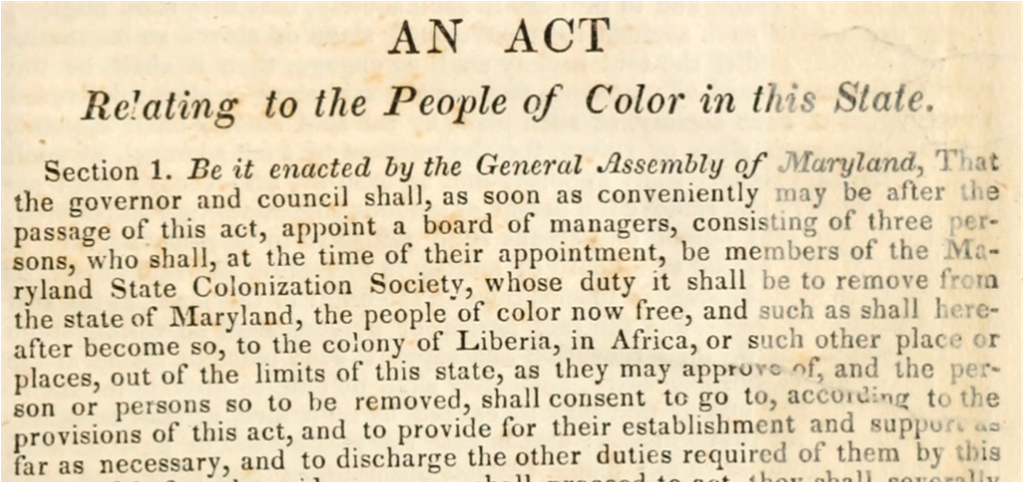

Two decades prior to Robert’s tenure there, Ashbel Green, President of both Princeton University, and the founding board of the seminary– and a domestic slave owner– wrote a statement of the relationship between the Presbyterian church and the institution of slavery that would be referred to as the official policy of the PCUSA for decades. Green declared slavery “utterly inconsistent with the law of God.” However, with twisted arguments, he then discussed the “paradox” of slavery and recommended some practices markedly short of abolition such as: exhorting masters to be kind to their slaves, encouraging slaveholders to teach them religion, sending free blacks to the newly established colony of Liberia, and “forbear[ing] harsh censure” against those who were trying their best to free their slaves. The statement made claim that a positive outcome of teaching religion would be to prevent the “evil of incitement to insubordination and insurrection.”

While Galbraith attended Princeton, he witnessed the culmination of a transition away from the ideas of liberalism and social reform toward conservatism– often referred to as Old School Presbyterianism. Some Presbyterians generally located in New York and western Ohio agitated for abolition and censure of Presbyterian slaveholders. However, in the 1836 convention, the General Assembly feared division if they were to either defend slavery or support emancipation and rejected anti-slavery and emancipation proposals. The year of Roberts graduation—1937– the Old School and the New School split into two separate churches over differences on doctrine, revivalism, and slavery. Slavery in the Old School was determined to be a political issue, not a church issue.

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t6b27zw9g?urlappend=%3Bseq=5

In the years leading up to the split between Old and New Schools, anti-slavery activism in the country became increasingly organized and in 1833 abolitionists in New England formed the American Antislavery Society. However, while leaders in Princeton Seminary extolled the evils of slavery, they still could not visualize a society where blacks and whites would live together peaceably. Faculty and board members and many alumni favored gradual emancipation and were leaders in the American Colonization Society (ACS). The organization opposed slavery but believed immediate emancipation (abolition) would be disruptive to the country and advocated emigration of free blacks to the American colony of Liberia, Africa. Some alumnae, as individuals, did participate in abolitionist activities and agitated for the end to slavery from the pulpit.

Archibald Alexander, first faculty member at Princeton Seminary and present while Galbraith attended, was one of the earliest and ardent supporters of the American Colonization Society. He wrote A History of Colonization of the Western Coast of Africa, published in 1846:

“Two races of men, nearly equal in numbers, but differing as much as the whites and blacks, cannot form one harmonious society in any other way than by amalgamation….. [which would take] a thousand years; and during this long period, the state of society would be perpetually disturbed …… Either the whites must remove and give up the country to the coloured people, or the coloured people must be removed; otherwise the latter must remain in subjection to the former.”

Interestingly, the same year Alexander published the treatise, he spoke at the inaugural service of Govane Chapel (seven years prior to Galbraith’s service at Govans, while he was still in Virginia). The Maryland State Colonization Society was an auxiliary of the ACS. Some contend that the conflict between conservative antislavery (such as colonization) and abolitionism helped kill the antislavery movement in the antebellum upper South. Alexander was one of the pillars of Presbyterianism at the time and so a logical choice as guest. Was his alignment with the ACS purely incidental to Govans choice as speaker?

As Galbraith left seminary in 1837, at the age of twenty-eight, he also left behind a long-held dream to be a missionary in India, due to health concerns. With a new wife, Mary, according to The History of Presbyterianism in Illinois, he instead “turned his attention to Africa as it was found at home and devoted much attention both to preaching to the negroes and to their instruction in Sabbath school.”

***Part II will follow Rev. Galbraith to Virginia and Baltimore.***

Contact Lea Gilmore (lea@govanspres.org), Minister of Racial Justice and Multicultural Engagement, to learn more and to become involved in Govans’ Racial Justice Ministry.